”Throughout the history communication and information have been fundamental sources of power and counter-power, of domination and social change.This is because the fundamental battle being fought in society is the battle over the minds of the people. The way people think determines the fate of norms and values on which societies are constructed.“

Communication, Power and Counter-power in the Network Society, Manuel Castells

Part 1 : Index

Politics of hidden internet interventionism

Neverending reality show of online media

Conquering spaces of public discussion

DDoS Attacks

Content Takedowns

Targeted attacks on individuals

PART2 : SOCIAL MEDIA BATLLEFIED, ARRESTS & DETENTIONS

Our story begins in a snowstorm. A long line of cars is stuck on the road for hours. It’s freezing and people in the cars start to panic. Response teams are there but the machines are still not moving to clear the road. At that moment, a military helicopter arrives. A man with no hat and wearing only jeans jumps out to the heart of the snowstorm, takes one kid, struggles to carry him through the deep snow and strong wind, and brings him back to the helicopter. That man is about to become the Prime Minister of Serbia and this will be one of his most memorable heroic acts campaigning for the seat.

Everything would have been great if only there were no public broadcaster (RTS) crew already waiting with cameras for this heroic act to happen, and a number of staff that helped to pick up the kid, bring him out of the car and hand him over to the future PM. Simply put, everything would have been great if this heroic act were more of a real life situation and less a TV show, an ongoing, never ending spectacle, a social relation among people mediated by images1, that will last for years.

The video is broadcasted as the headline on the national television and uploaded on its official YouTube channel. And that is basically where our story really begins. The uploaded video became the material for numerous parodies, mostly presenting PM as a wannabe Superman. But then at one moment, all those videos started to disappear from the YouTube. This event in February 2014 was the official first case of our newly formed SHARE Defense crew, a group of lawyers, cyber forensics and policy experts formed to watchdog, assist and study cases of attacks against our rights and freedoms in the online sphere2.

Politics of hidden internet interventionism

As framed by the media theorist Manuel Castells, we should not overlook the oldest and most direct form of media politics: propaganda and control. This is: (a) the fabrication and diffusion of messages that distort facts and induce misinformation for the purpose of advancing government interests; and (b) the censorship of any message deemed to undermine these interests, if necessary by criminalizing unhindered communication and prosecuting the messenger3.

Governments are now experimenting with more sophisticated ways of exerting [Internet] control that are harder to detect and document4. It is the goal of this text to examine some of those methods based on our local experience, and we believe that they are used or can be used worldwide in similar forms.

From our ‘Superman case’ three years ago until now, we have witnessed a variety of violations in the online environment in Serbia. Specific cases of breaches of online rights and freedoms that our small team has been monitoring are made of arbitrary blocking or filtering of content, cyber attacks on independent online and citizen media, arrests and judicial proceedings against social media users and bloggers, manipulation with the public opinion through the use of different tech tools, surveillance of electronic communications, violation of rights of privacy and protection of personal data; pressure, threats and decreasing the security of online and citizen media journalists and individuals. We filed more than 300 different cases in almost three years, and created a monitoring database that is a foundation for this analysis5.

Source : Share Foundation – monitoring.labs.rs

Our main interest in this analysis is to try to explore some of the forms and methods of interventions that different political actors or power structures can use to control and conquer online sphere. Here we will mostly speak about hidden, indirect actions, interventions done by the unknown actors, individuals with hidden or fake identities, companies without visible ties to government officials, political troll armies and troll lords, or even “artificial” entities.

As usual in our investigations we will try to quantify and visualise some of those forms and try to detect and understand some patterns.

– I –

Neverending reality show of online media

According to the media theorist Douglas Rushkoff, we live in the age of the present shock.6 Most of the information we get from the multiple sources simultaneously, at lightning speed, is so temporal it gets stale by the time it reaches us. Everything is live, real time and always-on. This is why narrative structure collapsed into a never ending reality show.

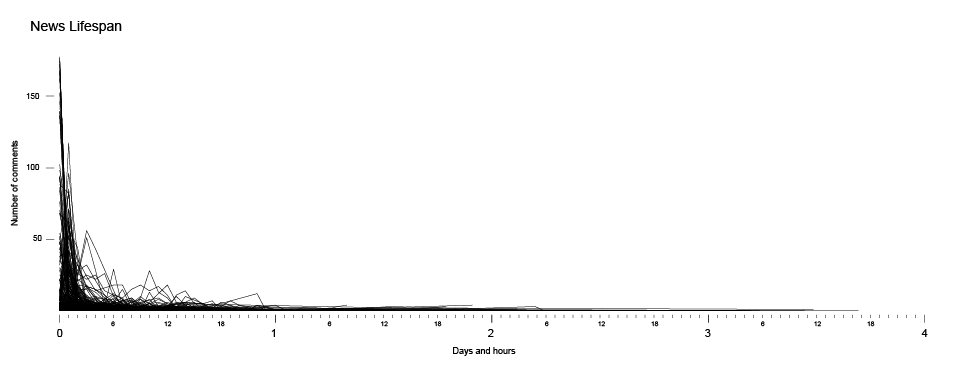

The lifespan of a single piece of information, a single piece of news in this flickering reality show, is short. According to our research7, an average lifespan of the news in Serbian online media is between one and two hours. During the first two hours, the news is being commented and shared, and then it disappears among the vast contents from the past, to be replaced by another short-lived news, and probably never to be seen again.

Source: Share Foundation – Monitoring of online and social media during elections ( in Serbian )

Source: Share Foundation – Monitoring of online and social media during elections ( in Serbian )

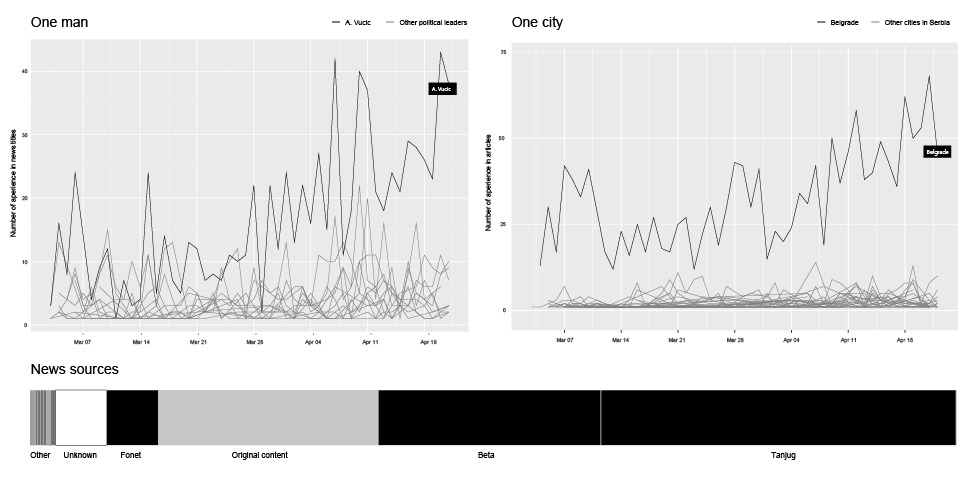

This ongoing open-end reality show, a stream of thousands short-lived news, has its own main actors and main locations. What we have here in our case is a strong domination of one main actor, a political figure (Aleksandar Vučić, prime minister of Serbia and the hero from the beginning of our story), and domination of one city, the location of this reality show (Belgrade).

SOURCE: SHARE FOUNDATION – MONITORING OF ONLINE AND SOCIAL MEDIA DURING ELECTIONS ( IN SERBIAN )

SOURCE: SHARE FOUNDATION – MONITORING OF ONLINE AND SOCIAL MEDIA DURING ELECTIONS ( IN SERBIAN )

According to our research, this supreme leader is playing a dominant role by far, managing to appear in over 40 news titles on 10 examined online media in a single day. Countless media statements and conferences, interviews and live acts are pumping the rhythm of his constant presence in our information stream.

This fast information production pace (as we can see on the horizontal bar chart of news sources), is fueled by three biggest news agencies in Serbia (Tanjug, Beta, FoNet) producing together more than 60% (black) of the news that are just being disseminated by the online media. The original content produced by the media outlet itself makes only one quarter (gray) of the analyzed news.

Politics is media politics, and affecting the content of the news on a daily basis is one of the most important endeavors of political strategists8. But, as we will see in the following chapters, conquering the field of the news content is just the first layer, first field of the battle over the minds and attention of the people in the networked societies.

– II –

Conquering spaces of public discussion

”In ‘normal war’, victory is a case of yes or no; in information war it can be partial. Several rivals can fight over certain themes within a person’s consciousness.”9

Information-Psychological War Operations: A Short Encyclopedia and Reference Guide

In not so distant past comments on the main news portals were still a place for the public discussions important for the general public in Serbia. But in recent years those places are being conquered by the armies of orchestrated entry level political activists, empowered with tools that allow them to use multiple identities, misuse voting mechanisms, distract public discussion and create fake picture of public opinion online. This information warfare doctrine, is known as “astroturfing”, or as some authors name it “reverse censorship”10.

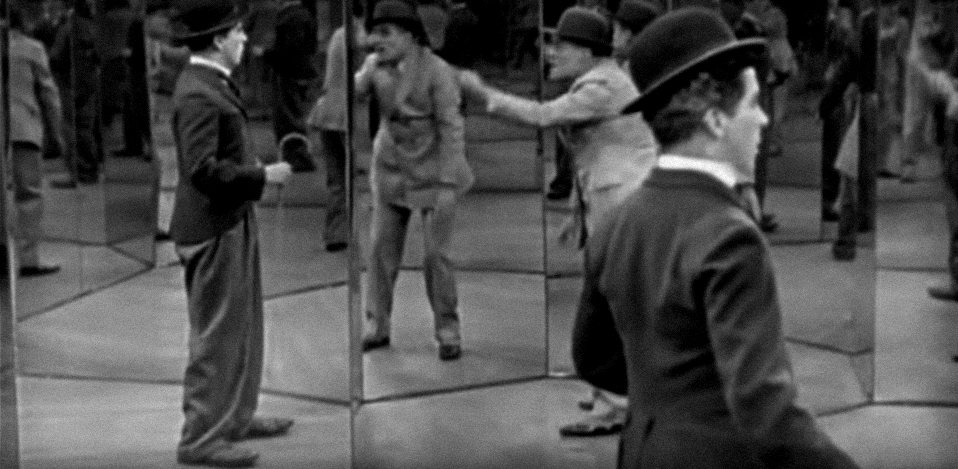

Mirror maze scene from the Charlie Chaplin movie ”The Circus” (1928)

Mirror maze scene from the Charlie Chaplin movie ”The Circus” (1928)

With inserting the multiple fake players in the public discussion, they created discourse filled with noise where real public opinions are being flooded, lost in the mirror maze of the artificially created and orchestrated political statements. By this, those places previously used for public discussion are losing their primary role and becoming battlefields for political soldiers equipped with various weapons.

As more and more places for open discussion are being conquered, there are less and less places where your voice as an individual can be heard.

On the other hand, we can believe that such practice is discouraging individuals to express their opposite opinion and participate in the discussion where they will be automatically attacked by many. As framed by Nietzsche, ”The individual has always had to struggle to keep from being overwhelmed by the tribe”. In our case, the tribes are even on steroids, their performance enhanced by different technical tools (magical potions of multiplicity and invisibility) acting not as headless crowd but as a targeted weapon of the information warfare. But, as the philosopher continues, “If you try it, you will be lonely often, and sometimes frightened. But no price is too high to pay for the privilege of owning yourself”.

Arms depot

According to a series of leaks11 published by the web portal Teleprompter.rs in 2014 and 2015, the ruling party SNS has been using (at least at some point in time) different types of software that could be used for astroturfing and other means of the public opinion manipulation. There is a special “Internet team” within the party, made of people with knowledge of PR, media, Internet and social media work. Some of them also hold public positions, like councilpersons at the City of Belgrade, or positions at the Office for Media of the President of the Republic. It is important to notice that the software has evolved to a more sophisticated tool, and since the last leak was published in 2015, we can assume that if there is any such software currently in use, it should be even more sophisticated.

Inside look into 3 known tools for manipulation with comments and votes :

Valter

SkyNet

Fortress

Gamification of the information warfare

An interesting aspect is that in this segment of the information warfare and public manipulation there is a system of gamification12 embedded in the process. Manipulation of the public opinion in this case is transformed into a game in which each user is being awarded with the points for each comment on a news portal. News portals are ranked by the numbers of points that user can get for one comment depending on the political affiliation of the portal. For commenting on the media portals close to the official government politics, they will get less points than for commenting in a more ‘hostile’ environment where there are other commenters with potentially opposed opinions. In cases of the media that are gathering public mostly affiliated with the ruling political party, there is even technical rule of limiting number of comments per user, not allowing them to get the ‘easy’ points.

Quantification of the troll productivity is the root of this gamification model. By quantifying their activity an information warfare general is able to control and command more efficiently and by gamification he/she is able to gain competitive atmosphere among players, to compete between each other or to compete against their own previous results.

The rewards for gamers stretch beyond pure psychological gratification, allowing them to climb up on the ranking list where they would gain a better status within the political party and, if they get lucky, they would eventually get a job in any of the public companies controlled by the members of the ruling party.

The style of the game

A combination of two distinct strategies of astroturfing developed within the Serbian online sphere in recent years, evolving from approaches that, based on their origin and geographical prevalence, could be referred to as Russian and Chinese. While the Chinese approach is marked by the strength of sheer numbers and mostly just cheerleading, the Russian one deals more with the personalised content, active political discussions and attacks on the “internal enemy“.

Polemics with the Internal Enemy – In his manual style blogpost Aleksandr Dugin, a Russian right wing political scientist, is proposing a rhetorical frame, which is quite similar to one that we can find in Serbian online sphere. “It is obvious that we have two camps in our country: the patriotic camp (Putin, the people and ‘US’) and the liberal-Western camp (‘THEY’, you know who)… A system of synonyms to be used in polemics should be developed. However, it should be kept in mind that such synonyms need to be symmetrical. For example, THEY call us ‘patriots’, and WE in response use the terms ‘liberals’ and ‘Westerners’ (Russian западники). If THOSE WHO ARE NOT US call us ‘nationalists’, communists’, ‘Soviet’, then our response will be: ‘agent of US influence’ and ‘fifth column’. If they use the term ‘Nazi’ or ‘Stalinist’, our cold-blooded response should be ‘spy’, ‘traitor’, ‘how much did the CIA pay you?’ or ‘death to spies’… An automatic patriotic trolling software, demotivators, memes and virus videos … or similar visual agitation materials for beginner level patriots could also be used against them.”

Polemics with the Internal Enemy – In his manual style blogpost Aleksandr Dugin, a Russian right wing political scientist, is proposing a rhetorical frame, which is quite similar to one that we can find in Serbian online sphere. “It is obvious that we have two camps in our country: the patriotic camp (Putin, the people and ‘US’) and the liberal-Western camp (‘THEY’, you know who)… A system of synonyms to be used in polemics should be developed. However, it should be kept in mind that such synonyms need to be symmetrical. For example, THEY call us ‘patriots’, and WE in response use the terms ‘liberals’ and ‘Westerners’ (Russian западники). If THOSE WHO ARE NOT US call us ‘nationalists’, communists’, ‘Soviet’, then our response will be: ‘agent of US influence’ and ‘fifth column’. If they use the term ‘Nazi’ or ‘Stalinist’, our cold-blooded response should be ‘spy’, ‘traitor’, ‘how much did the CIA pay you?’ or ‘death to spies’… An automatic patriotic trolling software, demotivators, memes and virus videos … or similar visual agitation materials for beginner level patriots could also be used against them.”  CHEERLEADING – The Chinese government has long been suspected of hiring as many as 2,000,000 people to surreptitiously insert huge numbers of pseudonymous and other deceptive writings into the stream of real social media posts, as if they were the genuine opinions of ordinary people. In June 2016, Harvard researchers published research13 exploring this massive government effort where, according to them, every year the so-called 50c Party writes approximately 448 million social media posts nationwide. But despite previous claims from journalists and activists that the 50c Party vociferously argue for the government’s side in political and policy debates, research showed that approximately 80% of analyzed posts fall within the Cheerleading category, 13% in Non-argumentative praise or suggestions, and only tiny amounts in the other categories, including nearly zero in Argumentative praise or criticism and Taunting of foreign countries.

CHEERLEADING – The Chinese government has long been suspected of hiring as many as 2,000,000 people to surreptitiously insert huge numbers of pseudonymous and other deceptive writings into the stream of real social media posts, as if they were the genuine opinions of ordinary people. In June 2016, Harvard researchers published research13 exploring this massive government effort where, according to them, every year the so-called 50c Party writes approximately 448 million social media posts nationwide. But despite previous claims from journalists and activists that the 50c Party vociferously argue for the government’s side in political and policy debates, research showed that approximately 80% of analyzed posts fall within the Cheerleading category, 13% in Non-argumentative praise or suggestions, and only tiny amounts in the other categories, including nearly zero in Argumentative praise or criticism and Taunting of foreign countries.

Polemics with the Internal Enemy – In his manual style blogpost Aleksandr Dugin, a Russian right wing political scientist, is proposing a rhetorical frame, which is quite similar to one that we can find in Serbian online sphere. “It is obvious that we have two camps in our country: the patriotic camp (Putin, the people and ‘US’) and the liberal-Western camp (‘THEY’, you know who)… A system of synonyms to be used in polemics should be developed. However, it should be kept in mind that such synonyms need to be symmetrical. For example, THEY call us ‘patriots’, and WE in response use the terms ‘liberals’ and ‘Westerners’ (Russian западники). If THOSE WHO ARE NOT US call us ‘nationalists’, communists’, ‘Soviet’, then our response will be: ‘agent of US influence’ and ‘fifth column’. If they use the term ‘Nazi’ or ‘Stalinist’, our cold-blooded response should be ‘spy’, ‘traitor’, ‘how much did the CIA pay you?’ or ‘death to spies’… An automatic patriotic trolling software, demotivators, memes and virus videos … or similar visual agitation materials for beginner level patriots could also be used against them.”

Polemics with the Internal Enemy – In his manual style blogpost Aleksandr Dugin, a Russian right wing political scientist, is proposing a rhetorical frame, which is quite similar to one that we can find in Serbian online sphere. “It is obvious that we have two camps in our country: the patriotic camp (Putin, the people and ‘US’) and the liberal-Western camp (‘THEY’, you know who)… A system of synonyms to be used in polemics should be developed. However, it should be kept in mind that such synonyms need to be symmetrical. For example, THEY call us ‘patriots’, and WE in response use the terms ‘liberals’ and ‘Westerners’ (Russian западники). If THOSE WHO ARE NOT US call us ‘nationalists’, communists’, ‘Soviet’, then our response will be: ‘agent of US influence’ and ‘fifth column’. If they use the term ‘Nazi’ or ‘Stalinist’, our cold-blooded response should be ‘spy’, ‘traitor’, ‘how much did the CIA pay you?’ or ‘death to spies’… An automatic patriotic trolling software, demotivators, memes and virus videos … or similar visual agitation materials for beginner level patriots could also be used against them.” CHEERLEADING – The Chinese government has long been suspected of hiring as many as 2,000,000 people to surreptitiously insert huge numbers of pseudonymous and other deceptive writings into the stream of real social media posts, as if they were the genuine opinions of ordinary people. In June 2016, Harvard researchers published research13 exploring this massive government effort where, according to them, every year the so-called 50c Party writes approximately 448 million social media posts nationwide. But despite previous claims from journalists and activists that the 50c Party vociferously argue for the government’s side in political and policy debates, research showed that approximately 80% of analyzed posts fall within the Cheerleading category, 13% in Non-argumentative praise or suggestions, and only tiny amounts in the other categories, including nearly zero in Argumentative praise or criticism and Taunting of foreign countries.

CHEERLEADING – The Chinese government has long been suspected of hiring as many as 2,000,000 people to surreptitiously insert huge numbers of pseudonymous and other deceptive writings into the stream of real social media posts, as if they were the genuine opinions of ordinary people. In June 2016, Harvard researchers published research13 exploring this massive government effort where, according to them, every year the so-called 50c Party writes approximately 448 million social media posts nationwide. But despite previous claims from journalists and activists that the 50c Party vociferously argue for the government’s side in political and policy debates, research showed that approximately 80% of analyzed posts fall within the Cheerleading category, 13% in Non-argumentative praise or suggestions, and only tiny amounts in the other categories, including nearly zero in Argumentative praise or criticism and Taunting of foreign countries. Quantifying contamination of the public discussion sphere

Except looking into the leaked material and software, we tried to search for some methods of quantifying and analysis the corpus of the comments and user votes in some of the largest online media outlets in Serbia during the pre-election period.14

Galaxy of comments

We have analyzed comments created from May 4th until April 21st 2016 from political sections of 5 biggest online media in Serbia (b92, blic, n1, kurir, telegraf.rs). Here we will present a few ideas on how we tried to visualise and understand different anomalies that can point out to potential forms of organised political astroturfing.

This is the comment universe in which every of the 105.227 comments is represented as a little circle. Bigger “stars” on this map are the same, identical comments that are appearing multiple times in different articles and different online media portals.

Here we can clearly spot that except political slogans (such as “Dosta je bilo”) there is a large number of identical comments, used by the different users and distributed across wide range of media portals and for different news articles.

Voting machines

Third field of battle, within news articles, after content and comments, are votes on the user comments.

Most of the websites we examined are allowing users to vote on the user comments. As noted before, there were several leaks suggesting the use of different tools and techniques for manipulation with number of votes on the comments. This is how overall picture related to votes on comments looks like in form of the 2 graphs.

We can clearly see that there are some anomalies, for example comments with more than 5000 positive or negative votes appearing almost on regular basis. Some comments even have more than 50.000 votes. Such big numbers are actually often in disproportion with number of unique visitors of examined websites.

To view how this dynamic of number of comments and votes looks like in time, we visualised them in a form of multiple bubble charts where every comment is one bubble and its size is determined by the total number of votes. This is attempt to capture the flow of the attention of the public and potential political voting and commenting agents.

But in order to explore in depth we should go a bit deeper at the level of a single article. We chose one article that based on our collected data showed some anomalies.

Looking into data On April 16th, 2016, the website of the cable news channel N1 /rs.n1info.com/ had approximately 28.92015 unique users during the entire day. But at the same time, a total of 183.630 votes were cast at the single news article (about opening of a textile factory in the 3rd largest city in Serbia) that we have examined. In order for this to work, each of the unique visitors of the website needed to go to the same article and to cast 6 votes. There are few other strange things hidden behind numbers. Until 10:54am there were approximately just a few hundred votes per comment, and then 4 minutes later it jumped to a 10 times higher level; it would remain more or less like that for comments posted until 2:35pm. Then it rapidly went down to just 50-60 really polarised votes per comment. This strange difference can be explained by an assumption that the examined news was probably removed from the homepage. But still, we don’t find reasonable enough explanation for the first jump. At the moment of the great fall at 2:35pm there was another interesting event. Being kind of late for the voting and commenting ‘party’, a user by the handle “dddd” posted 3 comments, one after another, with typical cheerleading style praising the great achievements of the leader. It’s hard not to think that this user just forgot to change his user name while trying to comment from different accounts.

In this example we can spot traces of (1) a number of votes are disproportional compared to unique number of users on website; (2) there are strange peaks in number of votes casted over time (3) there are examples of clumsy astroturfing. But another interesting point that we can read from this sample is that astroturfing is not only limited to the pro-government actors – it’s more like the common activity of different political options.

We examined three fields (content, comments and votes) of the battle for the domination in online media sphere and methods that can be described as a reverse censorship – contamination of the people attention and flooding with constant spectacle of constructed images of political propaganda.

In following chapter we will explore different forms of targeted and aggressive practice – attempts to censor content deemed to undermine interests and interfere with constructed image of the power structures.

– III –

DDoS Attacks

In 1998, art and media activist group Electronic Disturbance Theater launched a series of DDoS attacks on US and Mexican servers with custom based tool FloodNet, claiming this was a form of electronic civil disobedience in favor of the Zapatistas movement16. According to them and other media theorists at that time, a collective action of blocking servers of power structures can be understood as a digital equivalent of sit-ins, nonviolent form of protest, borrowing the tactics of trespass and blockade from earlier social movements and applying them to the Internet17. Almost 20 years later, this form of action is widely used by the decentralised affinity group Anonymous and other digital activist groups for numerous attacks on different targets including various government, religious, and corporate websites. But a lot of things changed during those years. DDoS attacks became available as a commodity, a service that you can buy in the dark, provided by the entities that have under their control huge botnets, networks of infected computers worldwide, ready to be used as a source of attack on any given target for a certain price.This is broadly used form of attack, since it does not require a huge amount of knowledge, or resources to be executed. Botnets can be rented online for as low as 20-30 USD, which makes this attack one of the most effective and common.

Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks are such attacks that exploit infrastructures called botnets by sending requests from them to a host (server) that is a target of the attack. In essence, these attacks make use of the hardware and software limitations of a server to handle a certain amount of requests. Every server, depending on its resources (bandwidth, ram memory, CPU etc), can handle a certain number of requests per second, once the number of requests goes above that number, the server gets saturated and if the number of incoming requests persists, the server will probably stop handling the requests and become unresponsive.

In Serbia, during the past couple of years, this method of attack has been often used by different actors, with the targets varying from online media and NGOs, to the website of the ruling party and even the website of the President of Serbia.

From electronic civil disobedience to bullying and censorship methods

The crucial difference is that in most of the cases that we analyzed, the targets were not elements of the power structure, but mostly small independent online media and blogs, websites that criticise the government, published texts that expose corruption or point out to the inefficiency of the government or the ruling party members. It’s symptomatic that such attacks happened usually just after publishing of stories or investigations that were not in favor of power structures. In those cases it is hard to define this practice as an electronic civil disobedience act, but more as a form of intended censorship, since the primary functions of servers that host media websites is to inform the public (well, at least in some cases). On the other hand, DDoS attacks are rather ineffective method of censorship, they last for limited amount of time, do not destroy content permanently and, what’s probably most important they often attract even bigger public attention. Taking this into account, perhaps we can think about those cases as a form of bullying, closer to traditional forms of pressure, intimidation and attacks on journalists, than as an effective way of online censorship.

This trend begun in spring 2014 with attacks on websites that deal more with investigative journalism rather than daily politics, most notably the CINS (The Center for Investigative Reporting in Serbia)18 and Peščanik (“Hourglass”, an independent online media outlet)19 being targets of DDoS. However, as the attacks became more common, all sorts of websites were targeted. At some point it even seemed as if one of the tabloids used the alleged DDoS attacks to generate some PR.

In this example we visualised server logs of one of the attacked websites, where we can see different traces, footprints of the attack that happened on February 12th, 2015. Every IP address is one horizontal line, but in this visualization,we hide the addresses to protect the privacy of the regular visitors

It’s really important to say that there still is no hard evidence that any government body or any political party is behind the DDoS against online media. The nature of the DDoS and the network structure is making those attacks almost impossible to track by independent researchers, and attackers are usually well hidden behind anonymity networks and multiple IP addresses in foreign countries. And even when there is a lead pointing to an individual or an organization, it is really hard to get information on who has ordered the attack. What we do have is the correlation between the content, political context and the attack.

Except DDoS attacks there are numerous other forms of activities, cases of technical attacks that we detected in previous years.

IV – Content Takedowns

It was at the end of 2013 that Serbian web witnessed a new form of brash activities from its underground.

The case of National Bank of Serbia’s Governor, Jorgovanka Tabaković, first started off as a more traditional censorship event. A local radio station from Novi Sad, the northern province capital, ran the story about the Governor’s daughter exploiting perks of having a powerful mother for her own benefits. The text appeared on “Radio 021” website on 9 December 2013, only to be promptly removed due to the political pressure “from above”, as the chief editor explained. Soon it became clear that the pressure had to change its form, since the text reappeared on a variety of personal statuses, blogs, and even some independent media sites. One of them, the Center for investigative reporting (CINS) fell victim to a hacking intrusion a couple of days later, when unknown perpetrator(s) forcefully removed just the ‘Governor’s daughter’ text from its website.

Though far from spectacular in deeds or consequences (both websites restored their content20), this case was one of the early signs that within the Serbian Internet underground a new type of activities is emerging. Driven not only by some general political convictions about rights and wrongs from the recent wars and loss of territories, this time illegal activities closely followed the ruling party political agenda.

The following year confirmed this impression, but with a twist provided by institutions that should have known their legal grounds better.

The blizzard that struck that little village of Feketić in February 2014 from the beginning of our story, made clear that the public broadcast service RTS, or the state-run television as it is more popularly known, was outsourcing its digital rights management. In this case, however, instead of flagging and delivering take down notices for reposted videos or audios of copyrighted folk singers, this mechanism was used to hunt down satirical versions of now famous video showing the then future prime minister campaigning in the snow with the help of a freaked out boy he ‘rescued’ from the storm. The event was also an opportunity to get familiar with the YouTube policy of removing contested material without any due process whatsoever.

It was particularly chilling to discover that this YouTube practice was exercised two years later, in August 2016, when Serbia’s own Ombudsman temporarily lost access to his YouTube channel21 for the unknown reason. As a response to an appeal, the Ombudsman’s office was offered to read YouTube’s Community Guidelines and Terms of Service. The email account that was used for servicing Ombudsman’s YouTube channel was also blocked, and although the incident was happily resolved in the end, it became clear that general terms & conditions of global social media prohibiting copyright infringement, hate speech or child pornography, became tools for the abuse of rights in censoring the internet.

Particularly in areas on the outskirts of the developed world, such as Serbia.

But, back in 2014 the local community was still naive, facing only traditional government action.

So, after the blizzard in February, there came floods in May. A town close to Belgrade, Obrenovac, was severely struck and left with dozens of dead, thousands evacuated and property destroyed. From the beginning it was clear that the public services was either overwhelmed or incompetent to deal with the situation, and the social media quickly turned into bulletin boards for volunteers, gathering aid, and exchanging information. This last point was particularly important since conventional media lacked resources or interest to cover the events from the spot. The latter group, formed mostly of pro government tabloids, ran false but click-baiting stories of hundreds of dead bodies floating around and Roma looting gangs on the loose.

When the first calls for accountability appeared online, the censors awoke. Several blogs and websites were taken down, to the extent that the OSCE representative issued a statement22. One page was deleted from the official city website, calling for citizens of Obrenovac to remain in their homes, after questions of adequate flood response were raised. Citizens’ testimonies were removed from the portal dedicated to volunteer aid, that was explained as withdrawal of possibly controversial content23. In combination of computer intrusion and ‘offline’ political pressure, numerous portals suddenly lost an open letter addressed to the prime minister, calling for his resignation. A group of social media users, bloggers, and online journalists started a petition against censorship24.

The momentum was lost when another social ‘disaster’ soon shook the internet in Serbia again, when allegations of senior officials plagiarism were published, and it became clear that the other branches of government were not planning to further investigate neither incidents surrounding the floods nor any other case of breaching online freedoms and digital rights. The mainstream offline media spinned most of these incidents as cases of technical ignorance and self-victimization of opposition supporters.

-V-

Targeted attacks on individuals

Although the attacks on media present a severe violation of the freedom of expression and access to information, when these attacks target persons, i.e. journalists, the assault is even more intrusive. The impact of those attacks is not as visible to the public and in many cases goes unnoticed, but for the journalists themselves they can cause fear, pressure and chilling effect.

Phishing is a form of attack in which the attacker spoofs (fakes) a legitimate website in order to obtain login credentials or other sensitive details. In the case of investigative journalist Stevan Dojčinović it was a spoofed Google account login page, distributed to him by a link he got into his email. Even though investigative journalists are well trained when it comes to physical and cyber security, the nature of their job is such that sometimes they need to pay attention to links shared by unknown sources, let alone the email addresses that look familiar (similar to the one of a colleague or an old source). Implementing a multiple factor verification solves this issue to some extent, making it harder for the attackers to get into an account, but it is not impossible to also spoof a phone number and get the SMS containing the security code.

The case of Miljana Radivojević, a Cambridge University researcher, and her emails was particularly interesting. The contents of a private email correspondence she had with a colleague that worked with her on a story about the plagiarised thesis of the Minister of Interior, Nebojša Stefanović, were featured on a talk show on a national TV, by the owner of the private university where Stefanović supposedly obtained his degree. Besides being illegal (on several different counts) the goal of this act was to destroy the reputation of Miljana Radivojević and discredit her in the public eye.

Another act of discreditation was carried in the case of Dragana Pećo, an investigative journalist. She regularly sends Freedom of Information Act requests to Serbian institutions electronically, using a standard form and a digital copy of her handwritten signature to compose the requests, which she then sends by email. At some point, she received a call from a PR representative of a state-run company that received a FOI request, signed and submitted by the journalist. As it would turn out, the identical request signed by the same journalist was sent to several public institutions, state and private companies, using an email account registered at Gmail that the journalist had never used, nor created. This was also a way of tampering with someone’s reputation, and assuming someone’s professional identity, which in the case of journalists can be considered an aggravated circumstance.

> PART 2 : MAPPING AND QUANTIFYING POLITICAL INFORMATION WARFARE : SOCIAL MEDIA BATLLEFIED, ARRESTS & DETENTIONS

Detailed monitoring data sets, results and analysis can be found here:

Monitoring of attacks

Monitoring of online and social media during elections ( in Serbian )

Monitoring reports

Credits

Vladan Joler – text, data visualization and analysis

Milica Jovanović – text

Andrej Petrovski – tech analysis and text

This analysis is based on and would not be possible without two previous researches conducted by SHARE Foundation:

Monitoring of Internet freedom in Serbia (ongoing from 2014) by SHARE Defense – project lead by Đorđe Krivokapić, main investigator Bojan Perkov and Milica Jovanović..

Analysis of online media and social networks during elections in Serbia (2016) by SHARE Lab – Data collection and analysis done by Vladan Joler, Jan Krasni, Andrej Petrovski, Miloš Stanojević, Emilija Gagrcin and Petar Kalezić.

SHARE LAB, October 2016

- Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle

- http://www.shareconference.net/en/defense

- Communication power, Manuel Castells

- “Whither Internet Control?” Evgeny Morozov

- http://monitoring.labs.rs/

- “Present Shock: When Everything Happens Now”. Douglas Rushkoff

- Analiza onlajn medija i društvenih mreža tokom izbora 2016. u Srbiji, SHARE Labs, 2016.

- Communication power, Manuel Castells

- Information-Psychological War Operations: A Short Encyclopedia and Reference Guide

- How the Chinese Government Fabricates SocialMedia Posts for Strategic Distraction, not Engaged Argument, June 1, 2016.

- Revealing another, much more dangerous bot-program, October 9, 2014

- Gamification uses game mechanics in a non-game context to reward you for completing the tasks.

- How the Chinese Government Fabricates SocialMedia Posts for Strategic Distraction, not Engaged Argument, June 1, 2016.

- Analiza onlajn medija i društvenih mreža tokom izbora 2016 u Srbiji, SHARE Labs, 2016

- Total real users: 28 920, page views: 119 397 and 44 159 visits in 24 hours. According to Gemius

- The Electronic Disturbance Theater and Electronic Civil Disobedience, Stefan Wray, June 17, 1998

- On Electronic Civil Disobedience

- CINS

- Peščanik

- Radio 021, CINS. The case further developed through the formal complaint the Governor filed with the Press Council, both against the portals that removed or lost their content into hacking, and against those that resisted pressures from above and down under. The complaint was dismissed.

- Social media as editors of public sphere: YouTube vs. Ombudsman, SHARE Foundation, October 4, 2016

- Government online censorship in Serbia worrying trend, says OSCE media freedom representative, May 27, 2014

- Internet sve pamti – Analiza Internet sloboda u toku vanredne situacije, SHARE Foundation, May, 2014

- U lice cenzuri, May 25, 2014